In recent times, there has been increasing attention on all forms of abuse and violence against women.

Many types of abuse are hidden from public scrutiny. Yet there is one that is easily visible: the acid attack.

Reshma Qureshi, pictured above, was attacked by an estranged brother-in-law. He had aimed to attack her sister, his ex-wife. This reveals one of the key attributes of these attacks: they are often perpetrated by somebody who the victim trusted.

When so many other forms of abuse are hidden, why is the acid attack so visible? This is another common theme: the perpetrator is often motivated to leave lasting damage, to limit the future opportunities available to the victim. It is not about hurting the victim, it is about making sure they will be rejected by others.

It is disturbing then that we find similar characteristics in online communities. Debian and Wikimedia (beware: scandal) have both recently decided to experiment with publicly shaming, humiliating and denouncing people. In the world of technology, trust is critical. People in positions of leadership have found that a simple email to the press can be used to undermine trust in a rival, leaving a smear that will linger, like the scars intended by Qureshi's estranged brother-in-law. Here is an example:

Jackson's virtual acid attack was picked up by at least one journalist and used to create a news story.

Some people spend endless hours talking (or writing) about safety and codes of conduct, yet they seem to completely miss the point. Most people don't object to codes of conduct, but we have to remember that not all codes of conduct are equal. In practice, the use of codes of conduct in many free software communities today looks like this:

If you search for sample codes of conduct online, you may well find some organizations use alternative titles, such as a statement of member's rights and obligations. This reminds us that you need to have both.

When we see organizations like FSFE and Debian trying to make up excuses to explain why members can't be members of their respective legal bodies, what they are really saying is that they want the members to have less rights.

When you have obligations without rights, you end up with slavery and cult-like phenomena.

History lessons

One of the first codes of conduct may be the Magna Carta from the year 1215. Lord Denning described it as the greatest constitutional document of all times – the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot.

In other words, 800 years ago in medieval England they came to the conclusion that members of a community couldn't be punished arbitrarily.

What is significant about this document is that the king himself chose to be subjected to this early code of conduct.

An example of rights

In 2016, when serious accusations of sexual misconduct were made against a Debian volunteer who participates in multiple online communities, the Debian Account Managers sent him a threat of expulsion and gave him two days to respond.

Yet in 2018, when Chris Lamb decided to indulge in removing volunteers from the Debian keyring (a form of shaming), he simply did it spontaneously, using the Debian Account Managers as puppets to do his bidding. Members targetted by these politically-motivated assassinations weren't given the same two day notice period as the person facing allegations of sexual assault.

Two days hardly seems like sufficient time to respond to such allegations, especially for the member who was ambushed the week before Christmas. What if such a message was sent when he was already on vacation and didn't even receive the message until January? Nonetheless, however crude, a two day response period is a process. Chris Lamb threw that process out the window. There is something incredibly arrogant about that, a leader who doesn't need to listen to people before making such a serious decision, it is as if he thinks being Debian Project Leader is equivalent to being God.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 10 tells us that Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations. They were probably thinking about more than a two day response period when they wrote that.

Any organization seeking to have a credible code of conduct seeks to have a clause equivalent to article 10. Yet the recent scandals in Debian and Wikimedia demonstrate what happens in the absence of such clauses. As Lord Denning put it, without any process or hearing, members are faced with the arbitrary authority of the despot.

The trauma of incarceration

In her FOSDEM 2019 talk about Enforcement, Molly de Blanc has chosen pictures of a cat behind bars and a cat being squashed in a sofa.

It is abhorrent that de Blanc chose to use this imagery just three days after another member of the Debian community passed away. Locking up people (or animals) is highly abusive and not something to joke about. For example, we wouldn't joke with a photo of an animal being raped, so why is it acceptable to display an image of a cat behind bars?

Deaths in custody are a phenomena that is both disturbing and far too common. Debian's founder had taken his life immediately after a period of incarceration.

Virtual incarceration

The system of secretly shaming people, censoring people, demoting people and running huge lynching threads on the debian-private mailing list has many psychological similarities to incarceration.

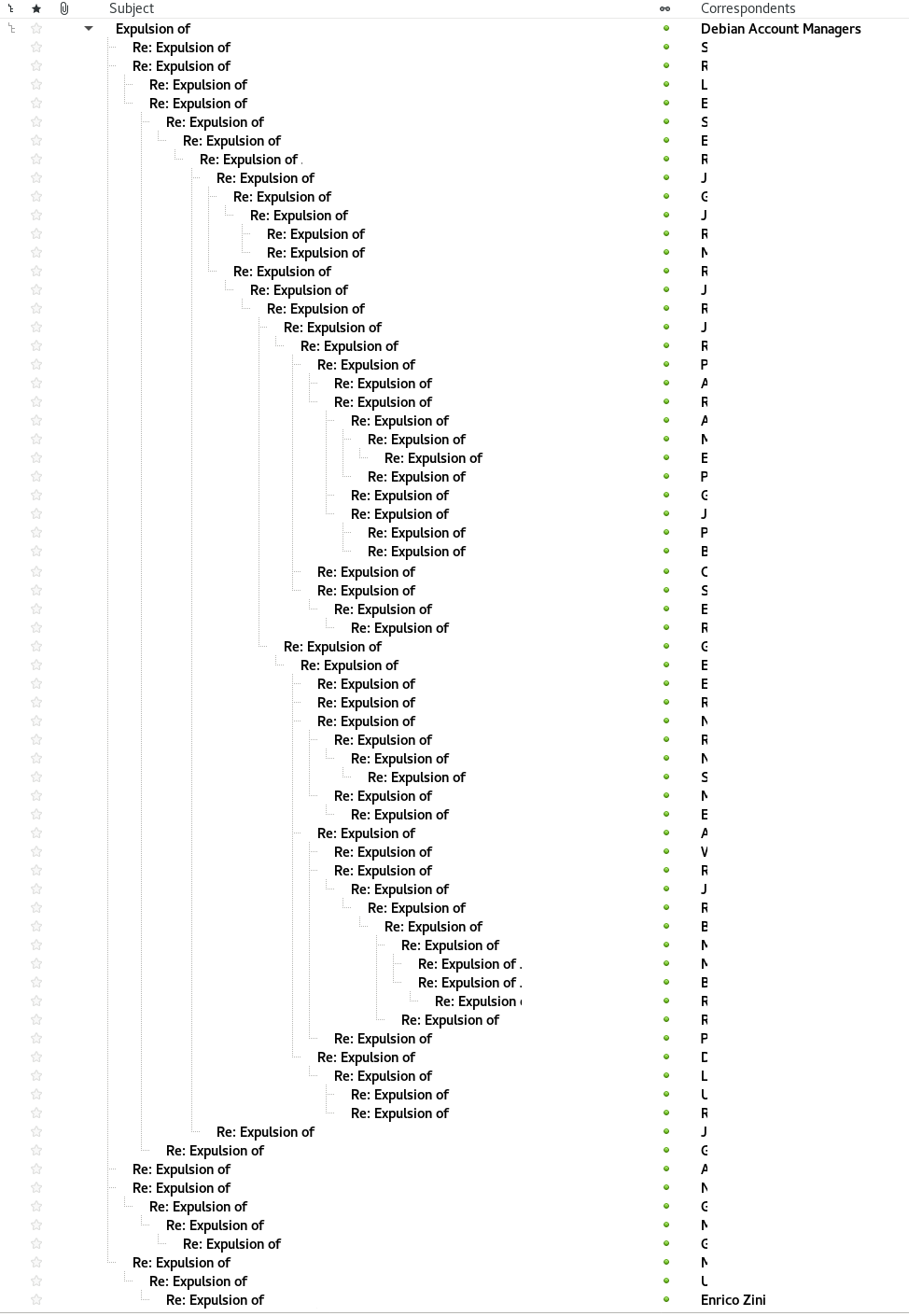

Here is a snapshot of what happens on debian-private:

It resembles the medieval practice of locking people in the pillory or stocks and inviting the rest of the community to throw rocks and garbage at them.

How would we feel if somebody either responded to this virtual lynching with physical means, or if they took their own life or the lives of other people? In my earlier blog about secret punishments, I referred to the research published in Social Psychology of Education which found that psychological impacts of online bullying, which includes shaming, are just as harmful as the psychological impact from child abuse.

Would you want to holiday in a village that re-introduced this type of cruel punishment? It turns out, studies have also shown that witnesses to the bullying, which could include any subscribers to the debian-private mailing list, may be suffering as much or more harm than the victims.

If Debian's new leader took bullying seriously, he would roll back all decisions made through such vile processes, delete all evidence of the bullying from public mailing list archives and give a public statement to confirm that the organization failed. Instead, we see people continuing to try and justify a kangaroo court, using grievance procedures sketched on the back of a napkin.

What is leadership for?

It is generally accepted that leaders of modern organizations should act to prevent lynchings and mobbings in their organizations. Yet in recent cases in both Debian and Wikimedia, it appears that the leaders have been the instigators, using the lynching to turn opinion against their victims before there is any time to analyse evidence or give people a fair hearing.

What's more, many people have formed the impression that Molly de Blanc's talks on this subject are not only encouraging these practices but also trolling the victims. de Blanc has become a trauma trigger for any volunteer who has ever been bullied.

Looking over the debian-project mailing list since December 2018, it appears all the most abusive messages, such as the call for dirt on another member, or the public announcement that a member is on probation, have been written by people in a position of leadership or authority, past or present. These people control the infrastructure, they know the messages will reach a lot of people and they intend to preserve them publicly for eternity. That is remarkably similar to the mindset of the men who perpetrate acid attacks on women they can't control.

Therefore, if the leader of an organization repeatedly indulges himself, telling volunteers they are not real developers, has he really made them less of a developer, or has he simply become less of a leader, demoting himself to become one of the despots Lord Denning refers to?